A few years ago, I turned in my Ph.D. dissertation and started working as a data scientist at a technology (SaaS) startup.

Since then, somewhere around once per month I get an email from someone in graduate school or in a postdoctoral research position looking for advice and guidance in making a similar transition; these folks are generally looking to hop from their current career path in academia or lab-based research to one in "industry" (as the institution tends to call it). In my experience, "industry" just means anything but academia. This is also a popular conversation topic at local Meetups. In general, I really enjoy this conversation! FYGM is not my style. And since I was 100% clueless about the "how" when I began thinking about the same transition, I can sympathize with a desire for more explicit examples and a little advice, and I'm happy to share both of mine.

However, even though I try to have these conversations with everyone who asks, I do not scale very well. In particular, since my advice has largely remained the same for the last couple of years (it's a pretty slowly-evolving system), I figured it would be worthwhile to write it down and see if the SEO/Google Overlords can help spread the knowledge more efficiently than me having infinity coffee meetings.

Disclaimer

This is not a general article about how to get a job as a unicorn data scientist. That is a well-trod path, and if you spend some time googling, you will find a never-ending list of suggestions. This article is about the ~5-step path that worked for me when moving from laboratory research science to the technology industry. It also includes some suggestions I'd probably make to an earlier version of me, given the chance.

Before getting started, I should be honest that this article is not representative of the nonlinear, indecisive, sometimes high-anxiety, and often back-tracking path that I actually took. And while it's valuable to acknowledge those processes (you may experience them too!), I don't think that story - which is really about the way my brain works - is the one that matters. Instead, these notes are the result of reflection and hindsight - a consolidation and compression of the things that seemed to work in my case. There's also a high probability of hindsight bias, so take it all with a grain of salt.

Foreword

The numbered sections below represent the portions of the journey that seem logically separated in my mind. But, importantly, they weren't completely serial. Real life is messy and these things were all quite mixed together for me. And while we're being honest, let's also acknowledge that it's possible none of this will work for you.

Ok, it's probably clear that I'm not a paid motivational spearker; if you're still interested, let's carry on. If not, thanks for stopping by. Go enjoy some panda gifs.

1: (Self) Research

Understand what you want, and what exists.

Let's start with some context. My transition began about two-thirds of the way through a physics Ph.D. program. I had chosen graduate school because I enjoyed the learning process, challenging myself, and - most significantly - I wasn't ready to be done learning about physics. I started with the assumption that I would end up like all of the professors around me, working on research and teaching.

I genuinely enjoyed the pursuit of making a dent in the barrier of human knowledge.1

But, as I was beginning to think about the next step in my life I had a growing sense that those same careers I observed around me were not the best fit for me. Furthermore, in what should have been the most important signal (but was not truly appreciated until much later), the actual odds of ending up in a tenured faculty position at some point are incredibly small.2 By this time, I had also come to understand (and entertain) the idea of pursuing research in a small, private lab setting. In the area around the University of Colorado, there are many private companies that have spun out of successful professors' research groups.

So, I worked my Google-fu looking for hints at precedent; what might the rest of the world think I'd be well-suited to doing next? I spent a lot of time doing this in the evenings and - if I'm being honest - when my lab experiments failed and I was frustrated. My browser history began filling with queries like "career options for a phd in physics," and "alternative careers physics phd." One HR rep at an engineering firm also suggested I learn how to downplay my impending PhD on my resume. I did not apply for a job there.3

As a physicist is wont to do, I tended toward thought experiments: what kinds of things do I enjoy? What would it feel like to do X every day? I began to hone in on this loosely-defined role of "data scientist" in the software and technology space, because it sounded like a great combination of tackling poorly-defined technical problems and potentially bringing value to a lot of people.4 Even better, it involved doing so at a much faster pace than my lab research. Encouragingly, I was also finding a number of articles that described having a background in physics as being a reasonable match for this role. While I don't think that a physics degree is provides greater preparation than, say, sociology, or economics, it was an encouraging idea at the time.5

Though not exhaustive, here are some things you might include in your thought experiment:

- What kind of work do you enjoy most?

- Writing software? Working out theoretical solutions to problems? Designing new models? Writing technical reports? Giving presentations?

- What kind of work environment do you prefer?

- A small team? A large one? Startup or corporate culture?

- How important are the company's values to you? If "very," what type of values resonate with you?

- Working on Wall Street comes with a different set of core values than working at a public health non-profit.

- How important is location? Is there a particular place you must be?

- Is working remotely a preferable scenario?

Identify the things that you'd like, dislike, and also those on which you're not willing to compromise.

Reflecting on the answers to questions like these is a helpful way to start and also an easier way to start drawing lines around what you want or do not want for your future. You might come out of this thought exercise with a list of companies at which you'd like to work, or maybe a list of duties and responsibilities you'd like. Either one is a win. Don't be concerned if you don't know the answers to these (and more) questions. As Stephanie Chasteen writes (beautifully, and incredibly geeky) in an article about her own career path into science writing:

I'm like bacteria... thermophilic bacteria do not "know" that the hot spot is "over there." They have no overall map of their surroundings to direct their movement in a straight line towards what they seek. What they sense instead is a local gradient - a small change, right next to them. It's a little warmer that way. They move slightly. They feel it out again. Move. Feel. Move. The resulting path is a somewhat jagged, but non-random, path toward the thing that they love. And so is mine... something perked up inside me. That way, it's a little warmer that way. And I took a step.

Suggestions for past me

Take these thought experiments as far as you can. Really stew on them. Try to understand what options are out there for your work environment: day-to-day responsibilities, compensation and benefits, growth and development opportunity. Consider the company's values, reputation, and trajectory. For a first job out of academia (which is likely to be a hard-turn career change), you may not be able to be picky about all of these. But thinking through how they align with your personal values is still worth it.

2: Double Duty

Assuming that you are currently employed in some way (maybe a research assistant or a postdoc), and assuming you are not planning to quit tomorrow, you're actually in a really great spot to start preparing for this transition. As you start to get a sense for the kind of organization or role that would work for you (see section 1), you will eventually want to start looking into the technical details. That is, identifying the skills, tools, and frameworks that are typically used.

The beauty of this phase is that you may get to "kill two birds with one stone": help you keep doing work at your current role, and prepare you to be immediately useful in your next role. It might mean installing new software on your lab computers, or maybe bringing in a personal computer. "Tools", here, is loosely defined; it might mean learning more (or starting to learn!) Java, or Scala, or Python, or Excel, or the bash shell, or a different kind of math, ... who knows. Well, actually you should know, based on your results from these first two sections.

If you've been doing research for years, you're likely already capable of doing magical things with software. In my lab years, I used things like LabView, Mathematica, Matlab, SPSS, Igor, OriginPro, Excel, and probably others I've forgotten. Universities are known for these massive, site-licensed software setups. You may have also written some extensions or customized plug-ins for these software tools, but that's unlikely to help you when you leave your lab. Aside from maybe Excel, I've never heard of anyone using these tools in a business setting.

For me, this step meant doing some extra work on my personal computer. In the lab I was doing a lot of analysis and approaching the start of dissertation writing. However, my work (software) environment was pretty comically far from where I spend my time today. In my lab, I used Windows XP systems, controled equipment (and did some analysis) with LabView, and did the rest of my analysis (and plotting) in OriginPro. From my googling and reading, it seemed the practitioners of the type of work that seemed most interesting to me were largely using R, Python, and some flavor of Linux command line. So, I started learning how to use those tools better, creating dissertation figures in R, manipulating some data in Python, and so on.

As far as how to learn these news skills, the internet provides. Depending on what level you come in, consider codecademy, MOOCs, open courseware, or just keep googling. For example, when I began learning Python, I started with codecademy and then moved to Learn Python The Hard Way.

Suggestions for past me

You're unlikely to ever be in a situation like graduate school again. Though you're not getting paid much, your schedule's flexibility is at an all-time high. Use this time to progress your learning as fast as possible. Once you start growing your new skills, put them to use outside of your regular work. Share the results. Use your newly-learned programming skills to write a tiny piece of software that's interesting to you and put it on GitHub. Then build something else and put that up there, too. Start writing about what you're doing, why, and how. Keep doing this until forever.

Sharing your interests and projects in this way will both make you better, and likely help you get a job.

Intermission: Networking

At this point, you should be gradually building the skillset you need to be capable of doing something on the day you arrive (if not, return to section 2). And, you're also hopefully getting a better sense of what kind of work you want to be doing and where (if not, return to section 1). It's time for the infamous "networking" step. This term gets thrown around pretty cynically, so let's just call it what it is: "talking to other people." For me, this step had the steepest learning curve, but was (and continues to be) the most valuable one.

While I won't go so far as to say this is mandatory, I think you're leaving a lot of possibilities on the table if you don't get out and talk to real people. I started by visiting my university's career services office and signing up for a bunch of "networking workshops." These particular sessions generally had two focuses: practice interacting with other humans, and understanding what you want out of a career. I'm pretty comfortable with the first part, and I had already invested dozens of hours on what I wanted back in section 1! To be fair, while these workshops weren't helpful for me, they were always packed full of people, so they could be helpful for you. They were all free events, and sometimes there was grad student bait free food, so it's not a bad place to start.

While my university career services events didn't prove useful, the local community more than made up for it. One of my top priorities (cf. section 1) was staying in the same area - roughly, the Denver Metro area. So getting out and interacting with people who were already a part of the technology community was hugely valuable. While I initially didn't know where to start, I did some googling to find local gatherings that sounded interesting, and looked for groups on Meetup. I also reached out on Twitter to people for information about events.

@jrmontag You'd probably love it. Tech talk among Boulder geeks. Jokes, relaxed atmosphere. Every other Tues at @AtlasPurveyors :-) #bocc

— Ef Rodriguez (@pug) October 26, 2010Then I just started going to events and talking to folks, asking them about what they did and where they worked!

In my mind, there's a crucial piece to this particular form of networking: not asking for a job. Maybe that's obvious to others, but I initially thought that was the main point of networking. It's true that the act of getting to know people in these contexts may actually lead to a discussion about jobs and open positions. But in my experience so far, the dividends are much higher when you just focus on getting to know who people are and what their interests are. This way, you're becoming part of a community, not just a local employee.

Suggestions for past me

Talk to as many people as you possibly can. Since you have introvert tendencies, this might be uncomfortable sometimes. Nevertheless, it will pay off in a relatively short amount of time (and hopefully continue to do so in the long run).

Make a few new friends; you're bound to meet someone with similar interests eventually. Learn who you don't want to talk to anymore. Connect with people online; at the very least, find them on Twitter. I can't say I've gotten any professional value out of LinkedIn yet, but give that a shot, too (I'm obviously biased, but I think Twitter is a highly underated professional networking opportunity).

4: Plan Your Escape Route

You've scheduled "D-Day" ("Defense"). Or maybe you're working on scheduling, and you've got a dissertation committee that's agreed to participate. Either way, there is a faint light at the end of the tunnel! At this phase in the 5-step plan, the personal decisions are at an all-time high. You'll have to contemplate your own circumstances, needs, and desires to make the "right" choices here!

In year five of my program, I was forming a committee and focusing the topic of my dissertation. It's common for people in the program to stretch six years into six and a half, seven, or more. Sometimes this is because their committee requires more work of them, sometimes it's because "hey, at least I'm getting paid for this and I don't have any other ideas." I was not interested in staying longer than necessary (see all previous sections). Coincidentally, my primary advisor had been planning to go on sabatical the summer after my sixth year. I didn't want to deal with the added challenges and frictions of communication from half a world away, so I was highly motivated to wrap things up.

As part of my efforts to meet people and understand local employment options (see section 3), I had reached out to a local data scientist who's work I enjoyed reading. A little research showed that he had been in the same graduate program I was in; that seemed like enough shared experience to possibly start a conversation. I sent him a short message on Twitter mentioning that I was transitioning out of the graduate program, was interested in his field of work, and that I appreciated the work he was publishing online. The Twitter conversation evolved into a coffee meeting, then a couple more, and a couple months later we were discussing the possibility of an internship.

Given the timing constraints I saw around me, I got to work designing my exit and getting my advisors to sign off on it.6 I would crank my lab research to 11 for one more semester (Fall), and then hard stop on experiments at the end of the calendar year. In the Spring semester, I would only take a half-time research assistant appointment, and would spend that time working on my dissertation in preparation for an official Spring graduation.

The other "half" of my time would be spent in a three-month (approximately semester-long) internship working with that data scientist with whom I'd had the coffee meetings (our conversations had gone well, and we were both excited about the opportunity). Importantly, there were no guarantees about what would follow the internship, but that was fine; I was looking for experience more than anything else.

Suggestions for past me

In this phase, I think it's safe to say that I benefited from a lot of good fortune. First, I was lucky that the first opportunity I pursued with ambition turned out to be a great fit for me, personally. Second, it was lucky that the company was both in a position to hire an intern, and that that process coincided with my search. I think it would be wise to be pursue a couple of these opportunities in parallel. Putting all your eggs in one basket is never a good idea; having more options is a more resilient approach.

5: Cut The Cord

Time is just about up. You're approaching the transition period, and hopefully you've worked out all the details with everyone involved. If you're approaching graduation, you've triple checked that you've met all the requirements and filed the paperwork by the right deadlines. How you get from one role to the next is a matter of preference, but there are many options.

For me, this step was fortunately pretty smooth. The internship had gone well: it was productive, I got along with everyone, and we did some fun work. As we approached the end of the agreed-upon three-month period, I was offered a a full-time position (contigent on defending my dissertation). I defended, turned in my work (photo at the top of the post), and signed the offer letter within a couple of days.

If you're moving into some position (contract, full-time, etc.) that you've already set up, consider taking a week or two to decompress. If the end of your research experience is anywhere near as overwhelming as mine, everyone around you will benefit from you taking a little time to unwind.

If you don't have a position set up (and no promising leads), but you're committed to being done with research, consider taking some time for self-study (MOOCs, textbooks, etc) or attending a "bootcamp". The market for these "data science bootcamps" has exploded in the last couple of years. Generally, you apply to participate and give an organization some number of thousands of dollars. In exchange, you get an intense 6-12 week classroom-instruction and project-based curriculum designed to introduce you to software engineering and common data science topics. At the end, most of these programs have guaranteed interviews with large tech companies.

It's probably too early to tell if these programs are "worth it" (by whatever metric is most appropriate). But it's clear that they have incredibly high placement rates upon completion, so the investment might be worth it to you if you can afford it. Generally, getting an interview at a major technology company is not trivial! In the interest of full disclosure, I applied to (and was rejected from) one of these bootcamps. But I have friends who were successfully hired after completing them.

Suggestions for past me

I think I did this step pretty well; I don't have much additional advice for past me. Taking a lot of time to ensure that I had considered all the details was crucial for getting support from everyone involved. While your graduate school advisors are hopefully supportive of your decisions, it was important to acknowledge that they may not have much advice or assistance to offer once I decided I was heading outside their circle of experience and expertise - academia.

Epilogue

That's a lot of words.7 If you read this far, great job - you deserve a cookie. Or an apple, if that's more your style. I hope some of these words are helpful to someone. At the very least, the next time someone googles "how does a physics graduate student become a data scientist", there will be at least one more bit of anecdata to provide some ideas and suggestions. If this was helpful to you in any way, let me know; I'd be happy to hear it.

Good luck with your transition!

Footnotes

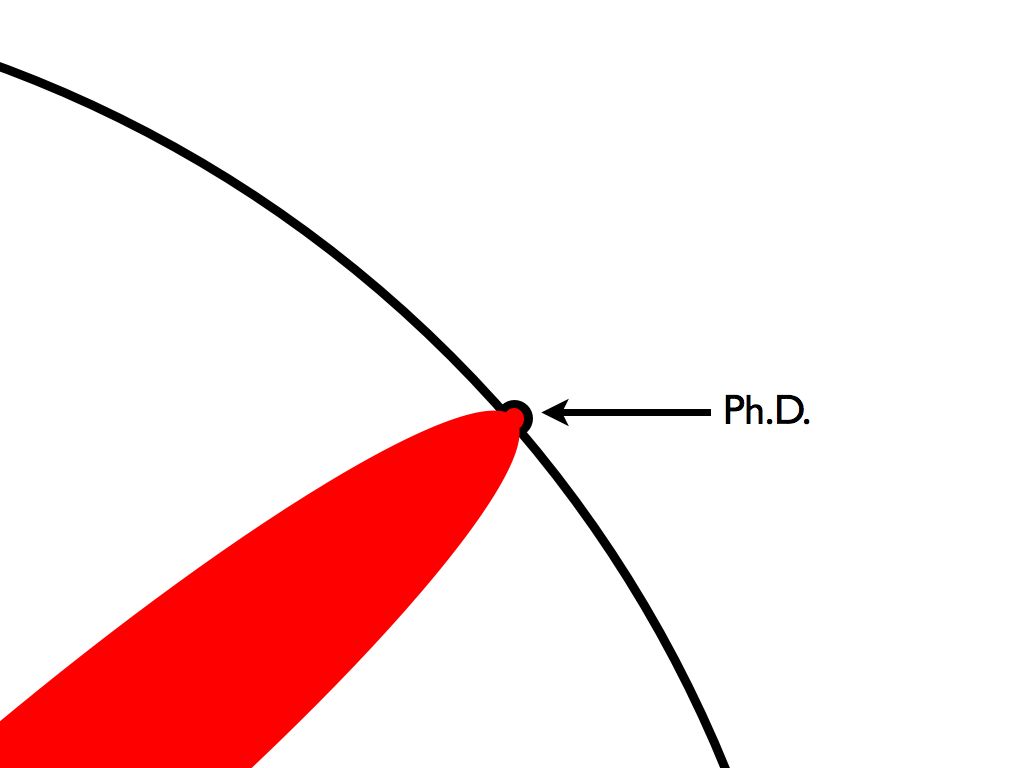

-

Matt Might, a professor in Computer Science at the University of Utah, created The Illustrated Guide to a Ph.D. to explain what a Ph.D. is to new and aspiring graduate students. Matt has licensed the guide for sharing with special terms under the Creative Commons license ↩

-

Unfortunately, the most recent data I could find on retirement rate is from 2008, but compare the two-year combined estimate of retirements from physics faculty positions (Table 1) (378), with the number of doctorates conferred from the same time period (Table 1) (2,959). That's almost a 1:8 ratio. Additionally, consider that the number of open positions is likely less than (at most, equal to) the number of retirements, and the excess of applicants held over from each previous year may also be applying for these same roles. Finally, consider that graduate enrollment in every field except education has increased since 2008 (Figure 6). I've obviously neglected the effects of subfield specialties (ie high-energy positions versus condensed matter), and many other subtleties. All that said, I think the point is still valid. ↩

-

As an aside, working through this process coincided with attending an annual APS March Meeting where I attended a session by Peter Fiske. He led a session based on his book exploring non-academic careers in science. I spent some time talking with him about non-academic careers for scientists and this effectively cinched the deal for me. I subsequently read his book (recommended!), and I'm still grateful for that fortunate encounter. ↩

-

This was before I heard the now-famous line from Hammerbacher about all the smart people working to get more people to click more ads. ↩

-

I would not say that physics, specifically, is necessarily the best field of study to prepare for the type of work I do currently. However, I do feel quite strongly that there are a few characteristics in a field of study that significantly improve the odds of success: training that is based in the scientific method, that relies heavily on mathematics, and that requires a significant investment of attention and effort in a poorly (or loosely) defined space. ↩

-

This design phase was not trivial. The details involved understanding and taking advantage of some odd corners in the graduate school rules. A big component of this process was convincing my advisors that my unusual plan was good for them, too. While the details were important for making it all happen, they're not that interesting, obviously specific to my program, and aren't necessary for the overall picture. ↩

-

Amazingly, the first draft of this post was dated 2015-01-23. My one-year retrospective was enhanced by an extra year's worth of experience. I've also found it harder to make time for extras like writing in the world of full-time employment. ↩